How does Amrapali define ‘contemporary craft’? How much does it vary from traditional craft?

From Amrapali’s point of view, we are always trying to design and make something ethnic. Even in the contemporary sense, it’s always ethnic chic. Ethnic is written in our DNA.

When it first started, Amrapali did a lot of tribal jewelry that became hugely popular. These pieces require exceptional hand skill and that’s what you will find at our Jaipur studio. I’ve noticed that most jewelry businesses are largely automated nowadays; we have machines too – but we really believe in working with artisans to get the details right. We don’t do enamel by machine, we try to improve the quality of the enamel from what it was before but the technique is old-fashioned. Our artisans like to sit on the floor and work; so even new contemporary pieces take a traditional approach.

Above: image | ground floor of workshop, enamel process

Can you cite a turning point where the business really began to grow?

In 2002 – during the time that we received an opportunity to be in Selfridges for their Bollywood promotion. I had been planning to go to America to study, but switched to London because of the business. Indian fashion – clothing, joothis, saris and bindis – was having its moment in the West. We always had international clients, but it’s a whole different game when you’re in a market (London) that’s selling to people from all over the world.

The Indian perspective towards the brand changed completely, which tends to happen when an Indian sees an Indian store internationally. Our red carpet requests were crazy at that point – we saw a change in the way people began to recognize Amrapali as an international brand and began studying it from the company’s perspective.

More recently, we finally got into the fine jewelry department at Harrods with the likes of Cartier, Tiffany, Bvlgari and Harry Winston. These are the turning points that have led to an integration in our mindset, and brought a cohesion in the way we see the fashion business.

Above: image | signage, cuffs in process

There seems to be a clear divide between the way you approach replicating traditional jewelry, versus creating contemporary collections. How does your design team create this new aesthetic?

Traditional old pieces from our archives are always the most important thing. In fact, Amrapali was originally a handicraft store for the first two years, started by my Dad, Rajiv Arora, and Uncle, Rajesh Ajmera. At that point, they were going to small villages all over the country trying to find pieces from pawn shops. They would buy a necklace with 20 pendants in it and make earrings out of those 20 pendants. Their logic was that they would make more profits, and also make 10 clients from that one piece. During this process they also made a small collection of silver articles which they had gathered from all over the place. The archive they built remains a precious resource for us and the starting point of all our collections today.

Above: image | Manish Arora for Amrapali

Even the Manish Arora collection came from archive pieces which were then redefined and redesigned. Even if the design team picks something new the base always has to be ethnic, I do not want any Amrapali piece to be confused with another aesthetic. We’re not trying to make something look European or compete with other manufacturing hubs.

We want to take from the roots of India and package or beautify it in a modern sense, so that we bring to the market what people need today. When people get married they want traditional jewelry, but it’s not appealing to wear the same piece your mother or grandmother wore because that could be a little too traditional. So what is a good balance? That’s what we try to create: the same story but in a way that makes sense for today.

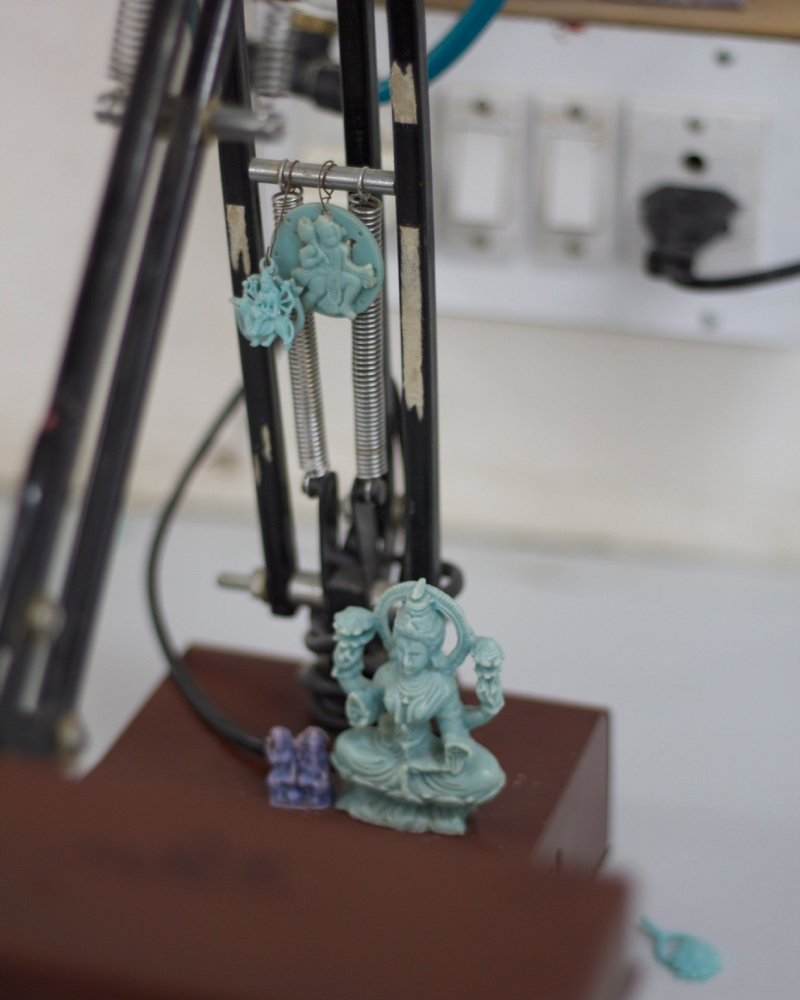

Above: image | wax cast idols at personal workstations

The 21st-century Indian consumer has a surfeit of brands to choose from. What do you see consumers gravitating towards, in terms of broad trends?

In my opinion, we have not even tapped 10% of the potential of India when it comes to e-commerce and social media. The best thing is that there’s a consumer for everything at the moment: for base metals, silver and gold because India is growing at every level. So the lower level is becoming mid-level, the middle level is moving toward upper middle and the top level is going crazy – there is tremendous growth everywhere.

Above: image | moulding process

Mentalities are changing too: People are buying what they like and not asking about the gold value or diamond value. Consumers understand that when you walk into a Sabyasachi or Anamika Khanna store, you don’t ask questions like kitne rupya meter hai? (how much per meter?) about a lehenga.

It’s the same way with jewelry: the consumer is becoming more and more aware that it’s about the idea, and finding a one-of-a-kind piece.

Above: image | wax cast idols

Does attracting and retaining your consumer base ever conflict with upholding craft techniques?

There are two sets of consumers. One consumer is aspirational and often looks up to celebrities for style cues. She could be someone who is extremely wealthy or a mid-level consumer, in both cases we see aspirational consumption as a growing trend. Consumers who are bothered about craftsmanship make up the other half. They are looking for something fine and intricate and inspired by old traditional pieces or art. Those people are less bothered about what looks good on them because they understand the value and know how to carry it very well. They’ll make sure something looks good on them. If it’s big they’ll find ways to scale it down or split it into two. The thought is not ‘how am I going to wear it?’ – the idea is to acquire it and then get the best usage out of it. These guys they have so much information already about these pieces, having bought and inherited jewelry over generations. They are into art and textiles, they are collectors and don’t need much convincing.

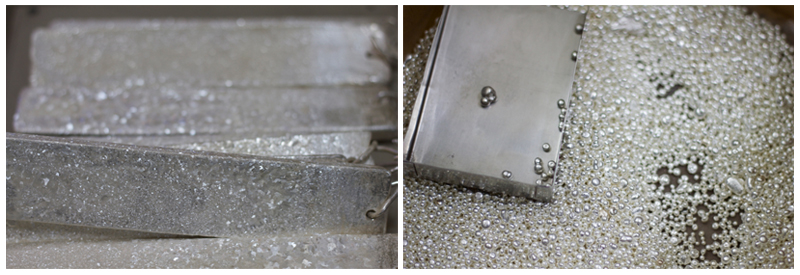

Above: image | polishing and casting, silver bars and silver grains

How aware is your design team of influencing the perception and image of Indian jewelry worldwide? Can you cite examples of how this is developed and communicated internally?

The Manish Arora collection was great because it tests what you think you’re capable of. We’ve done four with him now but at the time of the first one, our staff was completely thrown. I had workers saying that, “we can’t do this!” They had never done enamel in fluorescent pink and green and had no idea where to begin. There was also the matter of applying it on a curved surface without letting it drip. Generally what happens with enamel on a curved surface is that it gathers and is concentrated on one side. We had to put motors to create our own in-house machinery and rotate some pieces for four hours so that it didn’t drip.

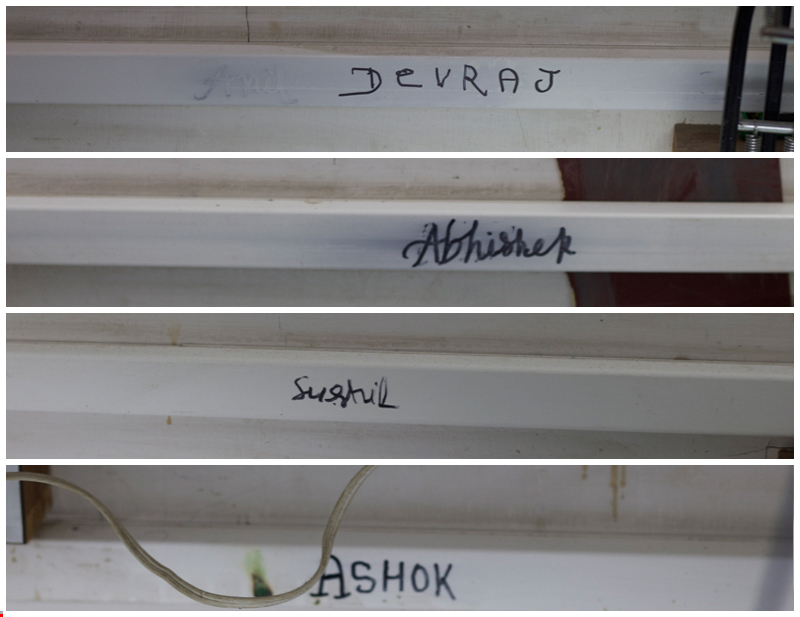

Above: image | marking workspace turf on electrical casing

Generally what happens with traditional craftsmen is they get upset when you tell them a clasp needs to be thinner because that’s how it’s done internationally. They want to work the way they have always been working. It’s a tedious process for designers to make them understand but when they see their work is loved it makes life a lot easier. Their own sensibility also changes.

The collection made its way to Paris Fashion Week and was a great success, as were the others. Our workers were so happy to see people appreciate what they had made internationally, it adds a whole different perspective for both our design team and the workers to see their effort appreciated the world over. When they relate to global qualities standards they understand why certain aspects need to change.

Above: image | polishing process

With rapid contemporization and hybridization in design, are you interested in defining and shaping what is authentically Indian (in terms of jewelry) in the years to come?

To be honest, our strategy is not about how to promote or take things to the next level internationally. When I tell my designers to make something, it stems from what I would like to wear or what I would like to see people wear. The idea is not to make a strategy and then work. Amrapali was always driven by passion; there was never a plan to reach a certain goal. My dad and uncle worked hard at what they did because they loved it, not solely to make money. I grew up observing their passion and that’s what I’ve got, that’s the culture here. Create and do whatever you want but do it properly, passionately, and do what you believe. I think if we are successful in being able to do what we think is correct in the right manner, it will be appreciated globally. As long as we have the guidance to understand fashion trends at every point and judge the moment correctly, we should be fine.

Above: image | adorned mannequin

We recently did a collection called ‘Dark Maharaja’ which is an example of how relative taste can be. I have lived in London for 12-13 years now and I’ve always been fascinated by the punks from Camden Town whose attire is black and leather, with pink and red hair. It got me wondering, ‘what is the underground scene of India?’ We have never had anything like that. So I wanted to create a collection which would represent this idea.

When you talk about Indian jewelry abroad, the first adjective that people use is ‘big’. They see Indian jewelry as bold, luxurious, high value… and luxury is associated with royalty – the Maharajas. But what about the evil twin? Or the brother who never became the Maharaja – the underground guy. He was the punk.

The whole theme was black, gold and red: red is ruby, black is silver and gold is 18K. The collection is very dark and edgy and our inspiration came from swords, the shield and vajra (a weapon signifying thunderbolt/diamond). A month later Rihanna was wearing it on the cover of W magazine. The moment you get that sort of validation, it makes me think I’m doing something right that looks pretty cool. The idea was not to define the Indian perspective of jewelry internationally. The idea was to explore what we feel is correct and has an edge to it.

What an absolutely intriguing and informative interview! The topic is fascinating and the subject is a font of knowledge. This story really captivated my imagination in an inspired way. Thank you.