I enter this dialogue as a creative individual, attempting to strike a balance between the contemporary (analogous to digital) and the traditional (analogous to analog) within the context of how we operate. I have always liked most things antique; places with character, crumbling walls and towers as opposed to sleek cosmopolitan neighborhoods; places exuding an old-world charm. I fail to understand those who find them tacky, dirty and “old” –hence meant for disposal or renovation. A lot of us who fall in this category (and I know there is a big category of “us”) would not embrace new developments with open arms as quickly as things continue moving towards digitization and mechanization. The context of our brand, and myself as a designer begins at a grass roots level. Ours has always been a context which stems from a local approach to global aesthetics. One where our weaver clusters around the country form the backbone, becoming the canvas behind each of our collections, rooted in the handloom sector of India. This forms our medium of communication. Without them, our “craft” is contextually irrelevant. The usage of handloom fabrics where the imperfections in the nature of the weave make each outfit unique, the garments that are produced at the end of each collection emphasize the feel of the “hand-made” and finds its place in any Indian or pan-Indian global context.

Ours has always been a context which stems from a local approach to global aesthetics.

One takes many things for granted in life, simply because they are readily available. For instance, the internet, with its progression and accessibility – and the fact that life is so much easier with it. When we work with the weaver clusters we have faced numerous instances where they are not remotely aware of anything regarding the internet. Not being able to share our ideas and sketches with them, having to courier everything can become tedious, especially when you are used to having instant access otherwise. I have always wondered, that perhaps this keeps their “craft” alive, who has not heard of the internet being a sepulcher and being a doom rather than a boon? If we speak of the internet or the digital world being a manifestation of all things “forward”, the weavers definitely need to be a part of this band-wagon.

One takes many things for granted in life, simply because they are readily available.

The question is – do we really want them to be “forward-thinking” or “forward-looking”? Cheap as it may sound, sometimes maybe we wish that it is better that the weavers are actually in their “backward” state (for want of a better word, really) because this state is one which gives them their creative license. There have been times when we have cribbed that the artisan sectors need to change and come up with innovative product lines, or more contemporary versions of their craft in order to make it more accessible and approachable for today’s contemporary global context; but then we are the same ones who end up saying their craft has become diluted because it does not look “traditional” any more. Our objective as a brand is to attempt to connect the past and make it more contextual in the present. Everything today is about “context”. Design in any of its purest forms is about creating a context and striking a balance with the products we make. This is true for the digital age, a designer who is specializing in textile must enter into interdisciplinary collaborations with other design specialties in order to build on their craft.

Design in any of its purest forms is about creating a context and striking a balance with the products we make.

The Jacquard loom was invented in the 18th century and has paved the way for a revolutionary change in the field of textiles. Lots is possible nowadays in terms of visualization, production and achieving the unimaginable. I remember during our weaving classes in NID (National Institute of Design), we used to get harrowed and butchered setting up our dobby sample loom with hundreds of threads intertwining with each other and trying to key the loom “shafts”. All this, at the cost of creating beautiful, gorgeous hand-woven samples which stood out because of being “hand-woven”. The Dhakai jamdani weaves that we explored last season were all extra-weft inserted by hand by weavers, who could have used jacquard looms but I did not want the “look” of a jacquard fabric because it was more-mechanized than the one by hand. I have an aversion for most things made by a machine; same as I have for prints made on fabrics, digitally. Handlooms give a wider scope to the maker to truly create and manipulate, which a jacquard loom does not. It is almost like assembly-line production; meters and meters of the same look. Almost being digitally cloned to look like each other. No two meters on a handloom can ever be the same, simply because there is a human hand involved. The imperfections in the nature of the cloth makes each yardage unique and one of a kind. In this age of mechanisation, this is how I wish to celebrate the hand-made, in my own little way.

No two meters on a handloom can ever be the same, simply because there is a human hand involved.

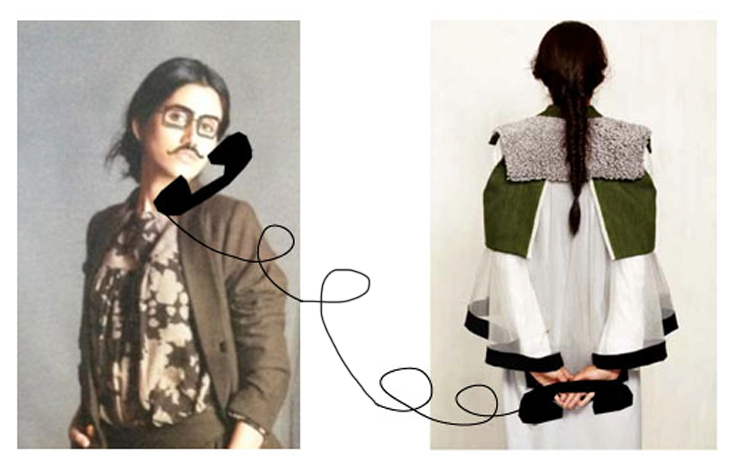

I think this is my way of challenging today’s machine-made world with most things looking like clones, to take a step back and enjoy the opposite spectrum ; of things made by hand. Of the touch of a human – hand. I try and celebrate this through our clothing lines. Indeed, mechanization has reinvented the way we look at textiles; this has been possible due to the digital and analog fusions which are defining the way fabrication is done nowadays. When I look at designers such as Issey Miyake and Hussein Chalayan, I admire them for their forward-thinking. What is commendable about Issey Miyake can be explained through his ‘Pleats Please’ collections launched in the 1990s. The innovation behind this was that the clothes were first cut and sewn together in sizes that were at least 2-3 times larger than the actual garments. They were individually heat pressed and sandwiched between sheets of paper. The final garment that emerged was with permanent pleats and a treat to the eye, in a proper size.

A product needs to stand the test of time and has to sustain itself in the global context when everything around us is changing ever so rapidly.

Much as I would love to hold on to all things made adeptly by hand, over the past decade or so, the access to new analog and digital tools have expanded a textile designer’s horizon and vocabulary. At the same time, I don’t know whether I sound back-dated if I proclaimed to not understand “digital-prints”, and that I will never use “digital prints” in our collections. To me, digital printing is an easy way out. Why a William Morris print is still so valuable and pleasing to the eye is because it is was originally hand-done and despite the innumerable copies and prints and editions of the Morris prints, the artwork has always managed to live up to the essence of the original. This is perhaps a good example of sustainability. A product needs to stand the test of time and has to sustain itself in the global context when everything around us is changing ever so rapidly. Only the concept and its context need to be viable and apt. If we take an analog printing technique, some may say this is an old conventional method of printing where printing is done due to direct contact with the fabric. One may argue that the technological advancement needs to be made for any form of printing to be economically viable during manufacture as it is practically impossible in this era of global mass production to product stocks within the short interval of the swiftly changing fashion seasons. To complement this fall-out, the industry resorts to digital mechanized means where the use of the “hand” / in this case “hand-made” is made negligible or at times done away with. The final product though might look “mass-produced” but some sections do not mind. In today’s age the textile designer does not work within a narrowly defined field of textile techniques but moves across the media and work methods of the textile discipline – from the overall concept to the concrete, tangible solution. A designer specializing in textile often enters into interdisciplinary collaborations with other design specialties where the choice of method and materials is determined by the concept and addressed in a broad spectrum of textile as well as non-textile materials. Trying to forge a balance is, of course, the way forward. One we try and strike everyday.

_________________

Paromita Banerjee is the Founder of Paromita Banerjee, based in Kolkata.

I met the lovely Paromita quite by accident in the Calico Museum in ahmedabad, and then twice more in the city and once in bhuj. What a charming and intelligent woman, and such an ambassador for indian textiles. I am looking forward to meeting up again in kolkota in october.