With its sinuous folds of fabric, the sari is a garment that is many things at once: modest and sexy, regal and prosaic, formal and casual. But above all, it is uniquely South Asian and essentially feminine. For India’s transgender community, these two qualities are paramount in making the sari their garment of choice.

“Sari is my culture, sari is my soul, sari is my religion,” says prominent transgender activist Laxmi Narayan Tripathi. “It enhances the femininity of the Indian body. It has always been the medium through which we express our femininity, our tradition, our culture, our Indianness.”

In the hijra community – a tradition which stretches back 4,000 years – wearing a sari is common, however not rigidly enforced. Rather, it is a sign of respect: for tradition, for seniors, for their guru. It is also a signifier of position: much in the same way that when an Indian girl starts wearing a sari it is a sign of her having reached a certain stage in life, when hijras officially become a ‘disciple’ they can usually be found dressed in saris. The hijra community is organised in a family-like clan structure, with a guru looking after and training disciples, or chelas, beneath her.

When disciples officially join a hijra community, there is a puja, and gifts are given – and these are usually saris.

“People in my community love saris, so it has become part of the community to give sari to your disciples,” says Tripathi. “I have always given saris to my children, to my disciples. Giving one is the highest honour to give a person.”

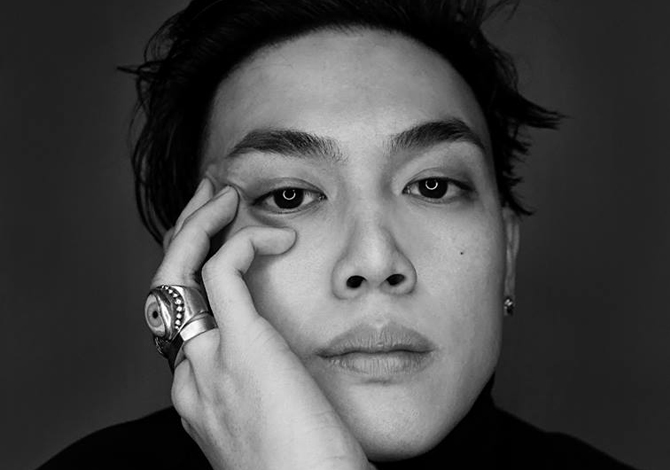

Above: Laxmi Narayan Tripathi image | DNA Research & Archives

As one of India’s most prominent transgenders she was born into an orthodox Hindu Brahmin family in Thane, on the outskirts of Bombay. She started life as a sickly and effeminate boy, confused about his gender and identity, however a supportive and loving family provided stability and before long, Laxmi was studying Bharatnatyam and sneaking out of the house to dress in a sari. “One day my parents called me in and said whatever you do, good or bad, do it from home,” Tripathi said in an interview with UNAIDS in 2015. “We don’t want to hear from someone else that you are going around in a sari, we want to see you getting dressed at home. We want to know the colour of your sari.”

Nowadays, Tripathi is one of India’s most recognisable LGBT activists: she has been involved in several NGOs including her own, Astitiva, which promotes the welfare of sexual minorities. She has represented Asia in international conferences and has appeared on television series including Bigg Boss. With her luxuriant mane of hair and heavily kohled eyes, she is immediately recognisable – and always, she is in a sari. “It’s a garment that can cover you entirely but also make you the most sexy person. It’s modest, but it’s also possible to look hot and sexy in a sari. It’s the most appealing dress for any eye in India,” says Tripathi.

Above: From the series #traindiaries on the ladies compartment of Mumbai’s local train images | Anushree Fadnavis

Her disciples can attest to Tripathi’s mastery of the garment. Rudrani Chettri, a Delhi-based transgender activist, described once seeing her changing from a suit into a sari in a moving car.

“We were on the way to the airport and Laxmi wanted to be in a sari. She somehow, sitting in her seat, managed to fold and pleat and tuck,” Chettri recalls. “When she got out she was perfect. I couldn’t believe it. She’s one of those who is a real expert.”

As a sari shopper, Tripathi is a self-described “freak”. “I’ll always buy more than 10 saris in one go. Never less than that.” Her favourite sari shops are dotted around the country: Chennai Silks in the south, Dakshinapan in Kolkata. Her favourite designer is Bhubaneshwar’s Dolly Parekh who handpaints sari silks with Orissa’s traditional pattachitra work. “I go mad for her saris, they’re so beautiful.” The importance of the garment to Tripathi takes on a new dimension when she speaks of her family. When her mother first bought her a sari, she had been thrilled. “It means she accepted me and my femininity completely. Yesterday my mother Whatsapped me photos of saris, asking, do you like this one, that one. Me and my sister share saris. My tailor also borrows them from me.”

Tripathi is considered more fortunate, for being accepted and able to wear a sari for the love of it. For other transgenders, however, family approval has not come easily and for them, donning the sari is often a bold social and political choice, explicitly setting out who they are inside for all to see.

__________

Anushree Fadnavis is a photojournalist with the news agency Indus Images and is based in Mumbai. Her personal work includes the series #traindiaries where she documents daily life within the ladies compartment of Mumbai’s local trains. She has been featured in publications such as BBC, Scroll, HT and The Indian Express. Her work on the transgenders community was also published by Arts Illustrated magazine.