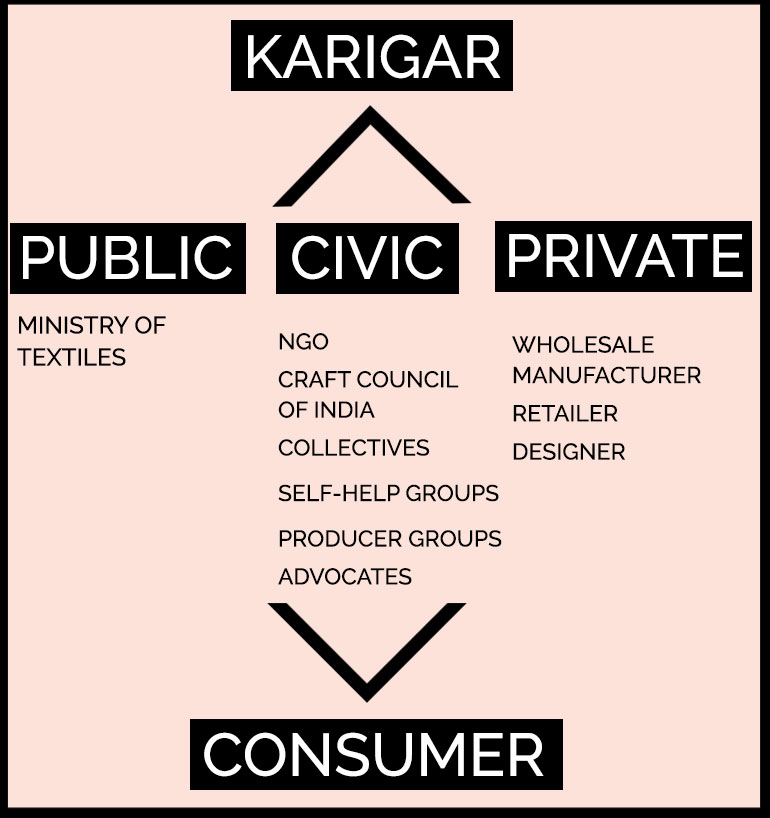

The hand and power loom dynamic: a daunting ecosystem for a modern karigar to negotiate in order to survive. Delving into this subject requires an understanding of many ground realities, and one of our primary intentions with this account is to cover basic context.

Often addressed academically with no room for the dilettante; the general public and even the design community can feel removed from the ongoing handloom/powerloom debate. As members of both, we realize there is rarely going to be a right time to pause and (re)familiarize ourselves with macro level information. As we wrestle with the immediacy of these issues, it’s becoming increasingly apparent that time is of the essence and a broader awareness will help in our individual goals.

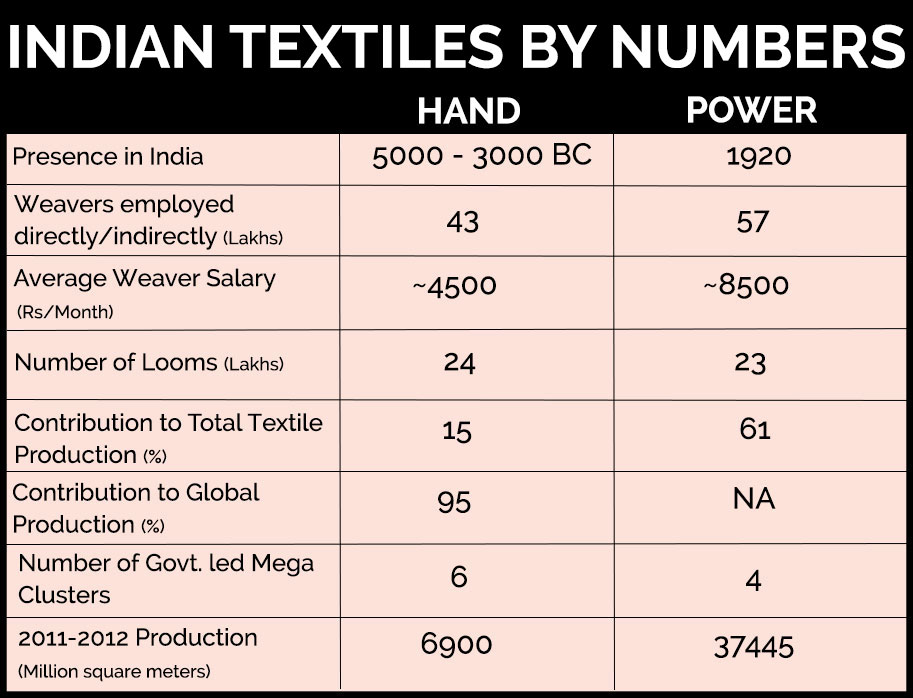

Championing hand VS power itself is a personal choice, to be made after an awareness of what each entails. It is not the starting point for debate, as is often the case. Understanding how they both co-exist as large players in India’s US$ 90 Billion textile industry is essential to moving forward.

Why does the majority of India’s 2nd largest employment sector fall into the low income segment? Why are there few numbers to reference these claims? Are we valuing craft correctly? What does this mean for the Modern Karigar?

As we begin our KARIGAR pursuit, it is becoming clearer that craft can only be truly covetable once a sustainable livelihood for the Karigar is ensured. Otherwise, it’s lipstick on a pig.

Handloom Synonymous with Indian tradition and culture, with the power to denote societal hierarchy, occasion and nationalism; handloom is considered, literally, the fabric of India. Accounting for 95% of global production, the sector remains shrouded in the pre-digital age and yet, contrary to popular belief, the sector is not resistant to change. Acknowledging technology is the way to the future, both digital and mechanized. Mr. Ashoke Chatterjee, Honorary Advisor to the Crafts Council of India and Ex-Director of the National Institute of Design (NID) states:

“Technology is required in the sector to lift the hand of the worker… not destroy it. Handloom is not against mechanization, but the USP of the loom is the hand.”

K. Satheesh Kumar, a handloom weaver from Balaramapuram, Kerala, says “A mundu (dhoti) that a handloom weaver makes costs Rs.400, while that from a power loom costs Rs.144. A woman earns Rs.150 per day from this one dhoti and she takes a whole day to weave it. You can see this is more than the sale price of the power loom dhoti. The power loom cloth making companies unleashed an advertising blitz on TV channels using popular Malayalam film actors in the last three to four years and they have completely captured the market. Even stores which exclusively stocked our hand-woven products say they will go out of business if they don’t stock the power loom dhotis and saris.”1

Powerloom Comprising of machine made textile, this decentralized sector has scaled quickly, playing a vital role in the Indian textile Industry, accounting for ~60% of the countries total textile production. Plagued by high power tariffs and power fluctuations, powerloom weavers produce by meters/day. Production affected due to power fluctuations remain a large concern, as weavers will not receive their earnings.

Umesh BN, a Powerloom Production Preparatory Manager at Himatsingka Seide Ltd was born in Dodhballapur and not from a weaving family, he entered into this profession after his father, a retired Canara Bank employee, began to manage looms. “The Government opened a textile park 3 years ago (Dodhballapur Apparel Park, Bangalore). It has become a power loom zone and forced weavers to buy modern looms through loans, subsidies and initiatives. It is a big project and not going well, 50% have closed. The reasons could be market didn’t meet expectations or the infrastructure wasn’t good. Weavers expectations have changed, they want to earn Rs. 300-400 a day and have everything simplified.

…My friends visited Surat out of curiosity, they researched on the net to find machinery useful to them, changed their machinery and now have good output and minimum breakage (of yarn). My passion is only about building a business, I have no affection for design. I want to sell product and get repeat orders. It is more cost effective.”

As an illustrative example of the continuing tension between both, we outline the most recent handloom ‘crises’:

In August 2012 a panel of technical experts working with the Planning Commission recommended that the existing definition of handloom be changed, in order to ‘make the sector economically viable’ and absolve ‘drudgery’ associated with weaving:

Definition of handloom as per the 1985 Handloom Reservation Act: “any loom other than power loom.”

Proposed change in definition: “any hybrid loom on which at least one process of weaving requires manual intervention or human energy for production.”

What this means Only one of the three weaving processes – beating (pre loom), shedding (on loom) and picking (post loom), is required to have a manual effort. The other can be mechanized, without the use of power.

-

This was viewed as a threat to the handloom sector because the powerloom sector could circumvent the definition by enlisting manual labour in one part, thereby benefitting from the various government policies benefitting the handloom sector (including powerloomed cloth being authenticated as ‘handloom’).

-

The handloom community objected and after months of discussions, Prasanna, a notable textile activist, led The All-India Federation of Handloom Organisations (AIFHO) into a nationwide Satyagraha (a nonviolent resistance). On responsibility, Prasanna notes: “We (the advocates) are partly to blame. We did not realize the danger; for the last 30 years handlooms have been systematically removed… in Maharashtra, there is not a single handloom left *. In Karnataka, more than 60% percent of handloom tradition is gone. For example, in Ilkal (Karnataka) – a famous sari center with a distinct weave that prevents powerloom from replicating it, there are only about 10 looms left in a village that used to have ~20,000. This is the situation in many towns in this country.We realized we need to speak to the people, in their local language (instead of the Government in English). That is when the Satyagraha began. It has been a big success but it cannot be led by weavers alone – they are a scattered community who has lost its confidence. The weaver does not have the confidence to lead this movement, which is why we have made it into a weaver/consumer led movement.”

-

In Jan 2014, the government retracted its proposed definition change stating “it is clarified that no change is contemplated by Ministry of Textiles, in (the) definition of ‘handloom’’2

Many believe that this effort was surrendered because this is an election year.

________________________

This brief does not take into account the many nuances and dynamics of the key players. There are also gaping holes of unavailable data, which many parties are working to fill.

Often, handloom appears the victimized party. Technology and its global impact have forced most industries to change, often giving a much needed rebranding opportunity to artisanal sectors. Handloom and powerloom both have an important role; unique enough to co-exist, leveraging the other.

Currently, efforts are being spent on defining identities. It’s an unsettling thought, given that the Modern Karigar born from this ‘civil war’ is likely to be focused on survival.

_________________

NOTES/REFERENCES

Atmosphere, part of Himatsingka Seide Ltd., is / was a client of the Border&Fall Agency.

** D. M Bawane, a senior executive officer from the Maharashtra State Handloom Corporations Limited commented: “There are 5000-6000 working looms in Maharashtra” 1. The Hindu, Handloom weavers oppose intrusion of power looms 2. Press Information Bureau, Government of India 3. Ministry of Textiles Annual Report