Architect Charles Correa designed Delhi’s Crafts Museum describing it as “experiencing architecture not as an object one looks at, but as an energy field one moves through.” Built between 1975 and 1990, it largely remained a vacant, dreary institution for decades – until the last couple of years.

Established in 1956 through the efforts of social reformer Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay, the National Handicrafts and Handlooms Museum stands at a corner of Pragati Maidan facing the Purana Qila. Spread over five hectares, the museum is founded on a mandate to actively support craft production and livelihoods. With a collection of over 30,000 artefacts the Crafts Museum boasts one of the country’s largest textile repositories.

New life has breathed into the Museum over the last five years: the presence of Cafe Lota and Lota Shop, the renovated gift shop, have put the institution back on the public radar as a destination of worth. With no reservations taken, lunchtime visitors often queue up to 30 min for a seat. This Rejuvenation Project, begun in 2010 through professionalization of services (moving from permanent government staffing to subcontracting specialized agencies), has led to improvements across the board. From monthly footfalls of 1820 in December 2010, the museum received 30,633 visitors in December 2014. Cafe Lota has played a major role in driving new traffic to this overlooked city treasure, and bringing back Delhiites who haven’t visited since a school trip 20 years before.

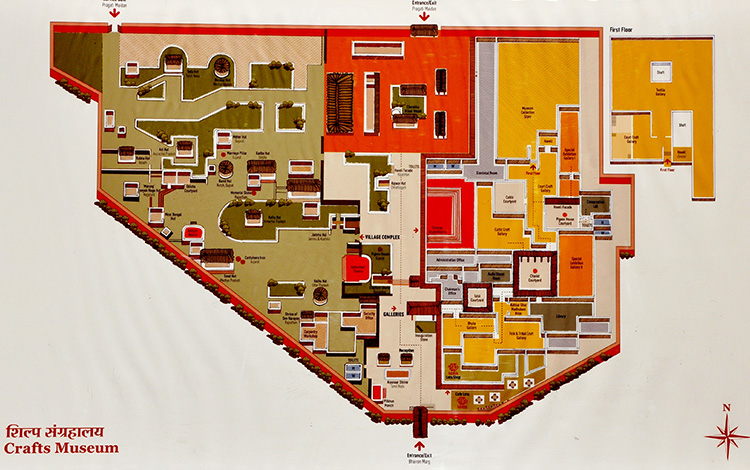

Above: A map of the Crafts Museum

Across the globe, institutions of historical, cultural or educational importance house restaurants and gift shops. New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMa) is home to ‘The Modern’, a Michelin-starred restaurant operated by Danny Meyer. Further uptown, visits to The Metropolitan Museum are often extended thanks to its expansive Met Shop. In the case of Crafts Museum, the revival has been largely through food.

While most of these institutions stand on their own feet irrespective, is it fair to assume art and culture is better appreciated with interludes of dining and shopping?

Like India’s numerous bureaucratic institutions, the Museum was long plagued by setbacks. Its management has undergone arbitrary shifts: from the Ministry of Commerce to Textiles to Handlooms to Handicrafts. Jyotindra Jain, director of the institution for 17 years till 2001, gave shape and momentum to Chattopadhyay’s vision. But between 2001 and 2010 the position of chairperson remained absent, with lamentable consequences.

On her appointment as Chairperson in 2010, Dr. Ruchira Ghose encountered falling roofs, dismal living quarters, and a disgruntled staff. “The library,” she shudders, “was a dangerous place.” Her work was cut out but nearly impossible to implement until financial and administrative powers were transferred. Fortunately, the Ministry of Handicrafts had allocated Rs 4.5crore for emergency works to coincide the museum shop and cafe opening with the Commonwealth Games that October. Neither shop nor cafe were Ghose’s top priority (nor were they finished on time), yet they remain the Rejuvenation Project’s two largest successes.

Above: image | Crafts Museum, Then & Now

For first-time visitors, it’s hard to imagine the Crafts Museum as a dysfunctional place. “The general rise in standard, frankly even clean toilets, bring people in,” explains Dr. Ghose. “It’s amazing, the difference it makes not just to consumers – designers and agencies offered assistance pro bono. Ray+Keshavan did graphic design for the signage, UNESCO surveyed factors to consider when planning change. We’ve been recipients for much generosity, because people are invested in the Museum and India’s wonderful crafts.”

The Lota Shop, situated prima facie, makes a major difference to footfall. Average sales have shown an incredible 250% increase since the old shop changed face: from Rs. 11,10,649 in February 2011 to Rs. 38,83,852 in February 2015.

As a joint venture with the Handicrafts and Handlooms Exports Corporation (HHEC) of India Limited, the Museum ploughs its 40% revenue share back into the shop. The store’s inventory is curated to reflect market expectations of quality and design as well as an aesthetic that relates to the Museum’s collection. Space has been carved out for regular exhibitions organised by the Museum, including a recent collaboration with jewellery brand Amrapali.

Above: image | Crafts Museum, Then & Now

Less perceptible but equally admirable are improvements further interior including Shilp Kuteer, perhaps the most congenial residence for craftspeople in Delhi. Artisans reside on location, benefitting from access to examples of some of the richest craft traditions the world has known. Karyalaya Kuteer, an office block for the Museum staff, has also undergone infrastructural improvements.

Still, the undeniable crowd puller is Cafe Lota. Recommended by local city guides, F&B search apps, culinary listicles, and celebrities, its contemporary spin on regional classics has the whole complex buzzing.

___________________________________

Chatter fills the sun-dappled courtyard that holds the Museum’s canteen-turned-restaurant. It’s 1:00pm on Tuesday afternoon and Rahul Dua, back from a weekly grocery run, can promise only his divided attention. With one eye on the steady stream of plates coming out of his kitchen, he traces Cafe Lota’s growth from humble beginnings in October 2013:

Dr. Ghose conceptualised an eatery that would be more than just a canteen, but 20 agencies turned down her proposal before Dua won the bid. “It’s very hard for seasoned restaurateurs to work with the Government. You cannot treat this like a restaurant in Khan Market or a posh locality, where you run the numbers from day one and use volume as an indicator of success. Organic growth for a place like this is vital,” says the chef. Influenced by India’s long-standing culture of State bhavans (special-purpose buildings for meetings or concerts whose regional-cuisine canteens are packed for lunch and dinner), his idea was to present clean, eclectic flavours with thought and flair.

Above: image | Crafts Museum, Then & Now

The first three months were difficult, spent twiddling thumbs and throwing away food. Risk-averse entrepreneurs had been reluctant with reason: the Cafe’s location within the Museum, and Government roots, posed practical problems. “There is beauty in being a hidden gem tucked away, but being a 48-over restaurant with zero parking—in Delhi, that’s suicide,” he says. The cafe now offers a valet service, as expats, tourists, and foreign delegates have helped the restaurant come alive.

The ratio of international visitors to locals has risen from 80:20 to 40:60. Dua explains why this is crucial: “We wanted to do more than cater to the tourist footfall. If the locals don’t come, you fail.”

With no air-conditioning or liquor allowance and Delhi’s extreme weather, among other deterrents, the focus rests almost entirely on the food and atmosphere. Lota’s well-priced menu changes constantly, encouraging return visits. Standout mainstays include the Palak Pathar Chaat (a crispy spinach tribute to the Indian love for chaat), Mutton Sukha with Coriander and Coconut paired with Ragi Appams, and Amritsar-style Tilapia crusted with Popped Amaranth and served with Sweet Potato Chips. The textured Bhapa Doi Cheesecake, topped with pistachio and almond slivers, puts a hallowed end to a lazy lunch. “With mostly word of mouth publicity, our monthly sales have doubled, even tripled, since 2013.” The restaurant has gone from having 30 customers on Sunday afternoons to 70, averaging a 30-45 minute wait.

Above: image | Beetroot Chops, ‘Bhaja Moshla’, Cream Cheese

Does the Cafe feed the Museum too? “Repeat customers may not want to visit the museum. But families who come here spend time with their kids in the galleries while they wait for a table. We feed 500 people on a weekend, and if 50 walk into the museum, it furthers the cause. If food is the way to do it today, so be it.”

Above: image | Kerala Vegetable Stew

A self-taught chef, Dua incorporates culinary memories from the places he has lived in – Bangalore, Mumbai, Aurangabad, Pune. He researched institutions he frequented in Mumbai, particularly Jahangir Art Gallery’s Samovar Cafe and Prithvi Cafe. His 10-member team, assembled from all parts of India, brings an authentic regional mix. Local flavours aren’t taken for granted: “If a Mangalorean eating here tells me their Konkan fish curry is better, I ask for the recipe.”

Above: image | Bhapa Doi Cheesecake

Dua’s tenet is to do Indian food the way it’s supposed to be done, instead of succumbing to the “European mindset” of substitution – “replacing a taco with a chapati” and calling it modern Indian food – which does little to take Indian food forward. His Apple Cinnamon Jalebi, a jalebi-like apple fritter dusted with cinnamon and served with coconut rabdi, illustrates his take on the subject.

While Dua admits that art and craft is not his forte, he understands community: “What I get out of it is the opportunity to change the face of government organisations, to change the way we use our free time.”

Above: image | Cafe Lota’s interiors

“Delhi has space – every museum here is seven or nine acres but they’re in ruins. Maybe food is the way to bring people back, a medium to force a change in perspectives.”

While the Museum and Cafe don’t directly collaborate, both believe in delivering an authentic experience whilst pushing cultural mindsets forward. Dr. Ghose corroborates, “For a museum to flourish, we need to engage, serve what people need today, what’s relevant to current tastes.” Interchange the word ‘museum’ with ‘restaurant’ and you get a somewhat generic answer to why people go almost anywhere nowadays. The earlier, bigger question – whether craft is a driver on its own, and how to plan so that it becomes one – seems to hinge on another overarching factor.

“A museum has to be run with vision and a long-term plan, not susceptible to political cycles and influence, if it is to become a museum of outstanding quality and international repute,” Ghose surmises. She emphasizes the need for autonomy in running public institutions, a sentiment Dua echoes: “Delhi needs institutions. They don’t have to be perfect, but they should stand the test of time.”

_______

1 The Guardian 2013