Khadi and Denim: two fabrics of distinct origins, histories and constitutions are now woven together in an inconspicuous but potentially significant marriage. One of the most exciting textile developments, this pairing is making inroads into the billion-dollar denim market.

Sturdy denim, once representing the tenacity of America’s working class is meeting India’s poetic khadi, developed as a fabric for the common man and signifying hope to a newly independent India. Denim however, has managed to progress from its utilitarian origins into a uniform for the chic and modern, appropriated equally by niche luxury brands while firmly belonging to the streets. On the contrary, khadi’s popularity has wavered, with a younger generation yet to forge a strong connection, often still considered the conventional cloth of the principled or intelligentsia.

Both are woven cotton, yet denim is highly technical and mechanized, whereas khadi relies on the dexterity of a hand that spins on an antiquated loom. India’s denim production is expected to grow to 1.0 billion meters per annum by 20151, yet there is nothing Indian about it: the technology is imported and designs are from Italian and American makers. Khadi, on the other hand, is India’s legacy and luxury – naturally washed, chemically unprocessed, hand-spun in much lower quantities – only 91 million square meters per annum in 2012-132.

The bottom line? Many revere khadi, but everybody wears jeans. From the khadi standpoint, joining forces with the apparel industry’s fail-safe cool kid is a strategic move. But equally forward thinking is the denim manufacturer who anticipates demand for an authentically homegrown, differentiated denim product. It appears that the genius behind combining khadi with denim lies in its appeal not just to khadi revivalists, but also innovators in the purest sense of the word.

Shifting Paradigms

Arvind Limited, India’s largest denim manufacturer, is a key player in bringing khadi-denim to market, having spent the last four years in R&D understanding the commercial, social and marketing angle that fits in with an of-the-moment East-meets-West narrative. Sharp branding of the three could propel the birth of a new textile, with a long life ahead of it.

The idea for this hybrid fabric first floated in the mid-Nineties, when a Rajkot-based organization Saurashtra Rachnatmak Samiti (SRS) began experimenting with samples. The resources involved in creating a commercial product are, however, an entirely separate proposition, and Arvind contacted SRS to pool resources for a larger scale operation.

The company’s internal product development lab has since researched and brought in consultants for extensive studies. Arvind’s Executive Director, Kulin Lalbhai, believes that he is seeing the birth of the product in its truest form only now, years into R&D. He explains, “Denim is quite a technical product, it requires specific treatments for indigo to react to the fibre. And then it needs to be woven in a certain way with a certain weight. It’s an incredibly difficult thing to marry khadi with denim technology.”

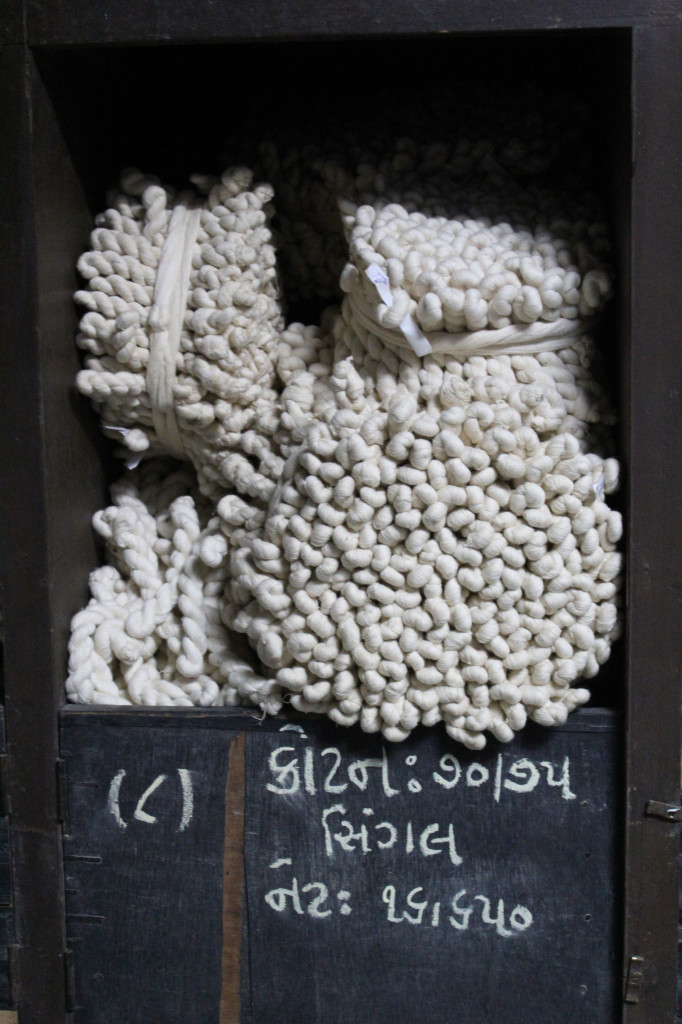

Speaking about the prospects and challenges associated with its developments, Lalbhai says, “Khadi and denim have very different supply chains. Spinning the yarn used for khadi is a completely manual process, done on the charkha, and so the major challenge with this product begins with how to source it. Arvind has been working with various intermediaries in Gujarat as well as direct sources to set up an entire supply chain to procure khadi yarn. Production is complicated as well because the yarn is inherently imperfect, and quite delicate. Retro-fitting the weaving and processing of this yarn with what’s required for denim manufacturing has been our second big contribution.”

The Value of Niche

CellDSGN – the design consultancy that has been collaborating with Arvind Ltd. on these developments – is in the business of shifting paradigms. Their denim and design expertise combined with Arvind’s technical backend has allowed for a richer exploration of weights, prints and chambray, while staying true to the basics of denim.

When Shani Himanshu and Mia Morikawa, who together make up CellDSGN, discuss the venture, one gets the impression that this endeavor is a labour of love. Apart from their involvement with Arvind’s R&D sampling, they have begun working directly with craftsmen on independent khadi-denim developments. Says Mia, “The process, from plucking the cotton to hand stitching, is so time consuming. Everyone touching the denim has to be engaged with it on quite a personal level, you can see their intentions for the fabric like a personal signature. It has been incredible to document how the artisans infuse their life within this inanimate object in such a spirited way, kind of the opposite of what happens with conventional denim.”

Himanshu has been wearing a pair of khadi-denim jeans handstitched by Virender, one of the artisans, since 2011. He says, “Once we went through the whole process it made us wonder why anyone would want a machine to touch it because it goes through so many hands…

…It takes a month to make the fabric, each with its own signature, character and weaver’s story. Being handmade it has an elasticity and comfort to it. There are certain stitches that have been designed from a hand stitch for denim to give it strength and flexibility – the crotch, for example, is stitched with chain stitch. A machine-made shirt is stitched with a single long stitch, which doesn’t have either. I’ve shown the fabric to Italian denim makers to hear their thoughts on it because they understand denim’s history: they felt the idea of producing this way today was maddening but were very happy that it was being done.” As a result, their brand 11.11 also produces its own in-house khadi-denim, entirely made by hand, retailing for Rs.25,000. The special edition case which carries the elements used in making khadi-denim is Rs.40,000. Speaking in depth about the artisanal production process, he says, “One person makes the entire stretch of fabric, there’s no assembly line. Denim is usually made with specialized machines that have different attachments for each stage, and it is assembled during mass production. In this case, one person stitches everything – like in a couture house.”

Perceptively, Arvind has also been working with designer Rajesh Pratap Singh, for whom weaving and R&D is core to his business. Rajesh has worked extensively with khadi throughout his career and began experimenting with natural indigo-dyed plain weaves five years ago. Over the past two years, he has been purchasing Arvind’s khadi-denim twill fabric. The alliance has grown into setting up a joint R&D unit to explore aesthetical and technical improvements that would make it easier to construct garments with. What excites him about the product? “It is hand-spun, hand-woven – completely hand made. It has a softness and beauty that comes from the natural indigo dyeing process, that involves no chemicals. And finally, it is intrinsically Indian.”

Prospects & Potential

If a commercial rationale is the primary yardstick by which to measure the progress of these developments, the present scenario shows plenty of scope for improvement. Given the limited ability to source the yarn, Arvind is currently producing only a few thousand meters of fabric. For the largest producer of khadi-denim in the world, this is hardly significant, even when placed within the context of its own overall production which averages nine million meters of denim fabric a month.

Its popularity might also be affected by denim preferences; khadi-denim doesn’t look like conventional denim. The loose, open construction of khadi fabric profits by becoming softer and losing any crispness – diametrically opposed to denim’s thickness and rigidity. To account for this, Himanshu mentions, “Khadi Gram Udyog is making and selling a polyester blend called polyvastra which has crispness and durability and sells much more than pure khadi. I’m fine with not ironing my clothes but how many people are like me? It’s a very delicate material that ages beautifully and becomes your second skin. But until we care about clothing the way we do about the quality of the food we eat, it won’t be understood.”

Rajesh maintains that continuous R&D, as well as quality control are the biggest challenges ahead.

Lalbhai says, “It would require placement in such a way that the consumer understands and appreciates its imperfections and qualities. That itself is a process because markets cannot absorb innovation that easily. You need the right brand with the right narrative, and usually such innovations work best when there is an aspirational product with a lot of credibility. There are lots of ‘ifs’ and ‘buts’ that go into it, and at this point, it’s still a process. I cannot say it’s something that has been established in the market because it will take time.”

Strengthening Communities

With the intention of making the process as close to source as possible, most recent developments have taken place directly with craft communities, instead of the Khadi Gram Udyog. Neither Arvind, 11.11 or Rajesh Pratap Singh are keen on calling it ‘CSR’ and when probed about the social angle, Himanshu responds, “I don’t think we are helping weaving communities, I think they’re very settled and we are happy that they welcome us. I would describe it more like strengthening existing systems and relationships spontaneously during our journey.”

Direct interaction is in itself a dynamic experience, and Himanshu has been faced with the task of setting up an interesting enough design challenge for the karigars.

For instance, Shamji, a master weaver from Bhujodi, a village in the Kachchh district of Gujarat, is quite adamant about representing the Kachchhi signature weave on anything he lends his hand to.

Although he has been involved with khadi-denim sampling, Shamji dismisses the fabric as “just a plain weave, without any distinct signature.” He explains, “What is important to us is that whatever we make should be identifiable with Bhuj. Nobody should wonder whether it’s from Allahabad, Bangalore or anywhere else.” Himanshu isn’t convinced this is entirely possible or desirable. “We like it when two different cultures or crafts meet, it happens kind of naturally. From Kachchh, Shamji sends his samples to the block printer, then to someone else for bandhni, and finally to the mainland. The piece keeps traveling, from a Muslim to a Gujarati house, each adding a new texture, colour … this helps us innovate. One thing I’ve learned is that you don’t have to show everything in a visible, obvious way. That’s what khadi is about: only the wearer knows they are wearing something special.”

Speaking of the wearer and responsibility, Lalbhai is of the opinion that he or she plays an integral, if indirect, role in building capacity within the craft sector: “One of the reasons why the entire supply base doesn’t exist or is underdeveloped is because there is no market. It’s our responsibility to bring the market at the right price with the right quantities so we can support this in a real way. Otherwise it’s going to be some very small, niche thing.” Consequently, the target demographic for khadi-denim is not necessarily young: “It is more likely people with evolved taste, with whom the social dimension resonates. But finally people who like to experiment with product.”

The Next Denim Revolution

Does Lalbhai believe Arvind Ltd has a revolutionary product in the making? “I think the biggest tragedy in India is that we have amongst the world’s richest legacies when it comes to textiles – there is no other country with the kind of diversity and talent that we have. Very few, if any, of our brands have really been able to bring this out. Unfortunately, it’s a very difficult process to link the arts and crafts legacy to a modern product basket – I don’t think there’s any formula or practice. To truly draw from this legacy and make a product that can really resonate with the modern consumer today requires an incredible amount of creative input and of course a business model that makes sense. Nobody has all the answers yet, and I’m not saying we have one, but I think that all these things need to fall in place if we have to bring this out. Otherwise initiatives like these will always be relegated to the small, ethnic, niche segments.”

Himanshu and Mia believe that it is more of an evolution: “Once you get into a pair, I don’t think you will like anything else. It’s always going to be expensive because it goes through such a long process – if you make it cheaper, you are cutting somebody’s wages,” says Himanshu. Mia continues: “In a world of shopping malls, big brands and cuttings costs it’s almost a kind of exercise: ‘is it possible to make something like this?’ I would say it’s quite a laborious thing. It’s not just something that comes from within, it comes from living in this world and wanting another option, not just for ourselves but to share with people.”

That said, the mandate here is not to make scale the absolute objective. What matters is that the scale mirrors what the supply chain can and should be, and that the footprint created has good impact.

Lalbhai elaborates, “Nobody can tell how big the potential is, but my hunch is that denim’s DNA is always going to be in rigid, cotton-based, strong, beautiful workwear. Some parts of that DNA resonate well with khadi and to that extent it will find a place for itself. It’s never going to become a two-million-meters-a-month category but that’s not what khadi should be, in my understanding.”

What makes the end worthy of the wait? “We are extremely excited to have succeeded in creating a final product, and the plans are to work with global brands to create a global platform – wherein India’s handicraft legacy meets America’s denim heritage.” The aforementioned narrative clearly seems to be the ability to innovate in a fairly traditional market. Lalbhai agrees: “Innovation is a core part of Arvind’s strategy, it has always been. We are the people who brought denim to India, and we’re also the people who constantly define what denim should be – so it’s our responsibility to push the paradigm.”

He does, however, realize that it’s going to take continuous innovation to stay ahead of competitors trying to replicate the fabric, assuming it is large and successful: “Exclusivity itself is impossible. The entry barriers – which is basically the ability to create this product in the state required – right now are so high. And we’ve been working on this for a reasonably long amount of time that I doubt anyone in the Indian context today is placed to do what we are doing. So we’re quite confident that for now we’re going to have exclusivity over the concept. But finally, it is more important to be the guys who make the best product and get it to the market in the right way. We’re hoping that the story and narrative is exciting enough for us to establish something truly worthwhile. That’s the key ambition.”

Given the history of khadi, and this enormous opportunity to re-engage with it, a lot is riding on these key players so that their efforts are commensurate with the response it deserves. A real sense of hope is palpable, but the question of what the “right way” to market it is still, for the most part, unanswered. Does it require an all-guns-blazing approach or a gentle but steady push, like the proverbial tortoise that eventually won the race? At this point, with much achieved and still ground to cover, Pratap has an answer that seems to sit quite confidently with him:

“Let it be a whisper,” he remarks, “this is the beginning, and we have to move forward slowly because it is neither gimmick nor trend. Let people understand it, and come back with their observations and requirements…

…Designers who are interested have access and can design into it. The Indian denim industry and Ministry of Textiles needs to decide where it is going, and in that respect, supporting the branding of khadi-denim allows us, as a country, to move away from being seen as just a cheap alternative where denim production is concerned. We’re talking long-term, huge employment advantages, and sustainability. Let’s not forget that, although everybody has a pair of jeans in their wardrobe, it is the most polluting garment in the industry. Here, we have a solution that is completely Indian and organic, environmentally friendly and natural. It’s solid, and the way I see it, it is growing. It’s not fashion – it’s more than that.”

_________________

REFERENCES 1 Sharad Jaipuria, President, Denim Manufacturers Association, India 2 Khadi Village Industries Commission (KVIC) 2012-13 Report

Hi,

I really loved your Denim Khadi Jeans concept. I would like to know where can i see and buy them in Mumbai or any other way.

Thanking You,

Chetna

sir I like all khadi Products

where can I buy khadi dinem jens