Claiming Narratives – Responsibilities Towards Histories?

Early last year, a design critic from a major international daily, writing on Indian design after attending a design event in Mumbai, wrote about how ‘…it must be said that design came to India only in the early 1990s…’. Today, when Social Design becomes a fashionable topic in design discourses, what about the path-breaking grass root communication design interventions sweeping rural India through the 60s? What about Dashrath Patel’s industrial design products in the 70s, that took from traditional methods of stacking and kitchen usage unique to India, and transformed these through new materials? And at a time when India desperately seeks international cross-overs in fashion, what about that pivotal moment in the mid 80s, when Asha Sarabhai collaborated with the legendary Issey Miyake on a label called ‘Asha by Miyake Design Studio’, using the best examples of Indian textile hand-craftsmanship; An Asian – Asian connect, between two contemporary cultures with a deep, common, shared past?

It would seem that a part of the problem here lies in an inability to understand ‘design’ in a culture, where a word for it in a local language does not exist? That perhaps even today – in this part of the world – creative making comes from a long tradition where such perceived divisions between ‘art’, ‘craft’ and ‘design’ do not exist on ground or philosophy, or that multitudes of technologies work in relation to each other and not always against. It would also seem that a part of this problem lies in Indian popular design’s blind imitation of trends in the Americas and Europe, leaving little scope for newness on the one hand, and on the other India’s grave, present inability to address its own design needs in most relevant ways. The crux of the problem however, may lie in our inability to give importance to our own – us protagonists’ – historicities? Is it not important to know where we’ve come from to know where we are going? Can design practise or expression in fashion truly innovate unless their commercial avenues have complementary non-commercial spaces to ideate and reflect? Don’t trade fairs need curated shows as their counter-parts? When would it seem high time to have India’s own design museum? To begin with, perhaps even, India’s first gallery devoted to showcasing the best of its design?

…are we local designers, writers on design and fashion, commentators on its role in India’s narratives, often spokespeople for its importance to our own – and the world’s – imaginations, talking to each other enough?

The emergence of India- as a potentially important future market for the world – has kick started a spate of initiatives to understand the country through its market, through the immediacy to grasp what design here means. From Kalaghoda to Lower Parel in Mumbai, from Kasturba Gandhi Marg in Delhi to High-Tech City in Gurgaon, design research centres funded by international companies and cultural organisations are opening up increasingly to feed the world’s interest in what makes it tick here. But are we local designers, writers on design and fashion, commentators on its role in India’s narratives, often spokespeople for its importance to our own – and the world’s – imaginations, talking to each other enough? Are we fighting enough to create spaces for healthy interactions on our own practises? And is it already too late to premise the generation of more reflective platforms for archiving, curating and writing about Indian design and fashion?

An eminent fashion editor stares at me blankly when I mention even a more recent exhibition Global Local, in 2004, which travelled to seven cities in India and was the first such major show of contemporary India design – In Bhopal, Right-Wing activists protested against Manish Arora’s use of gods and goddesses in prints, and the show later travelled to the Victoria & Albert Museum in London and received the biggest viewership a show received there that summer. For academicians-students interested in looking at Indian fashion from the sociological-anthropological point of view, no book since Emma Tarlo’s Clothing Matters comes to mind. And this was written as far back as the 1980s! While analyzing the role of clothing in India’s history, she focuses her research on changing responses to clothing among women in the state of Gujarat, and how ‘regional’ dress was given up gradually in favour of the more ‘national’ salwar kameez… It would appear only natural that for a country with the kind of diversity, and on the constant cross-roads of dynamic synergies, we would have emerged more vast bodies of work to observe changes? More rigorous a nature of responding to evolutions in making? More critical an attitude towards the need to debate?

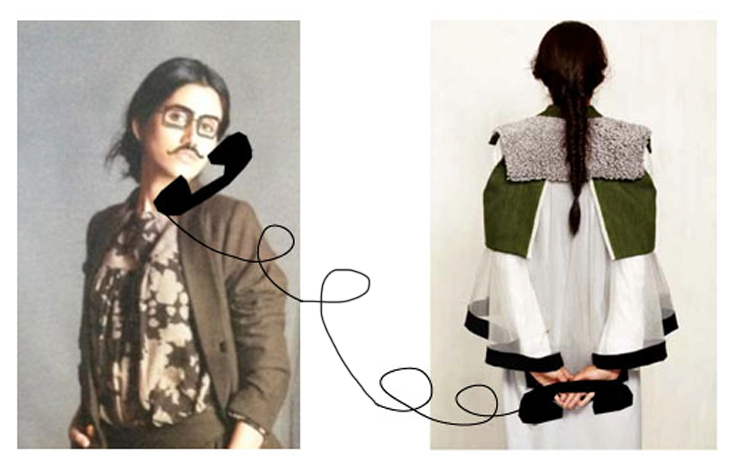

This minimalist approach to design using paired- down Indian handloom textiles and simple, western cuts, often found us immediate success from international buyers and agents, while the Indian market only gradually woke upto us as the number of expatriate clients increased, and as more Indians moved back to the country from abroad having been used to such ‘functional’ forms.

What are the urgencies in raising these questions? A few years back a colleague and I reflected on ‘us’ textile designers from NID seemingly, belonging to one larger aesthetic from India. This minimalist approach to design using paired- down Indian handloom textiles and simple, western cuts, often found us immediate success from international buyers and agents, while the Indian market only gradually woke upto us as the number of expatriate clients increased, and as more Indians moved back to the country from abroad having been used to such ‘functional’ forms. It was of course no surprise to us then, that coming from an educational background which favoured ‘apparel’ as a name for what can mean to be a course in ‘fashion’, not one from us had attempted successfully an entry into bridal Indian wear. That in the long run one were more likely to be remembered by international museums for their ‘idea’ of India, rather than mainstream markets here.

It was through the first time on a skype chat with Helena Perheentupa, now in her late 80s, a Finnish designer who came to India and set up NID’s textile design department, that the reasons for this became possibly clearer: As with NID’s product design and communication design programmes, which had been based on Bauhaus in Germany and the Basel School of Design in Switzerland respectively, India’s foremost modern textile design education pedagogy was based on looking at Indian decoration, with the precision of a Scandinavian? That the new forms which emerged as a mélange between such European sensibilities and Indian textile hand-craft traditions – and which were to fuel design trajectories for decades to come – did not celebrate its visual and material excess which had renowned India for centuries earlier in its textile trade with the world?

We might realise, for instance, that in the frenzy today – of the mass of young designers working with Indian textiles – Indian fashion’s biggest moment may have already come from a voice where these notions of identities were left completely? That what we do today, may have been done in the past already? That, perhaps, the best may have gone already?

It may be a matter of another set of conjectures, why NID itself, while having been funded in its inception by American Capitalists’ money – through funding agencies– who saw that a newly independent country like India in the 50s could emerge as a market for its industrial manufacturers, and therefore must be ‘cultivated’ in the use of ‘modern consumer products’; eventually became enchanted with utopian ideals of Socialism and Communism, and plunging itself into the cause of India’s craft revival, became capable largely of addressing only elite audiences with the spare time for such romances. Or that, close to six decades since NID’s beginning, most parts of the country have rejected such aesthetic ideals of Bauhaus and international modernism, in favour of its continuing fascination with over-indulged decoration. To me, these reflections – sometimes digressingly I admit – ultimately bring home the question of where in design, do our references come from? That before we start addressing the world, we must arrive at our own terms.

The future may remember us for what we do today if we care enough to give ourselves time. Not for posterity alone though. We might realise, for instance, that in the frenzy today – of the mass of young designers working with Indian textiles – Indian fashion’s biggest moment may have already come from a voice where these notions of identities were left completely? That what we do today, may have been done in the past already? That, perhaps, the best may have gone already? Or give us a sense of what we’ve missed all along…the elusive waiting to be occurred, that India’s biggest moments may lie ahead in an untenable future? And as far as the 1990s are concerned, we may remember them as not the beginnings, but as mere periods of transitions alone in a long, long trajectory of crazy creativities!

_________________

Images

1) Abraham & Thakore advertisement: (L) 2003, Elle Magazine India, (R) 2002, Elle Magazine Italy

2) The Nizamuddin West flat of interior designer Shona Ray from the 1970s, Delhi. Shona was among the first few designers with contemporaries like Riten Majumdar and Ratna Fabri who brought back the vogue of using Indian hand-craft in urban interiors, at a time when references to such design were mainly European. Photographed by Madan Mahatta Courtesy: Gita Wagle Chinwala & The Design Project India

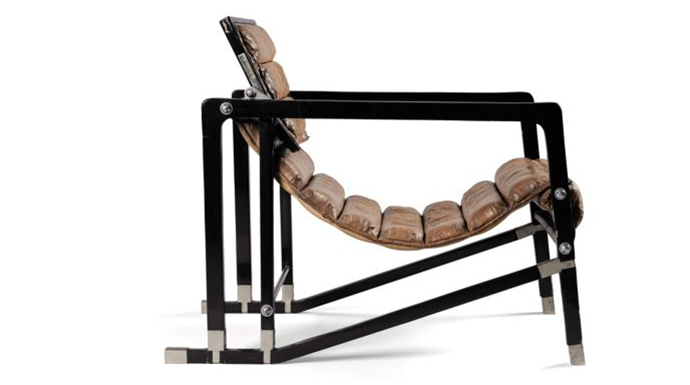

3) Chair designed by the avant garde designer Eileen Gray for Manik Bagh, The Maharaja of Indore’s palace, and which were used in the 1920s-30s. The palace’s interiors were designed by Eckhart Muthesius, a German architect from the Bauhaus. Courtesy: Sotheby’s

4) (Left) Outside view of a building in the Capitol Complex in Chandigarh, designed by Le Corbusier, (Right) Interior view of the State Assembly in the Capitol Complex. This is a rare image which shows a tapestery designer by Corbusier, and which was produced in a workshop set-up in India. Photographed by, and Courtesy: Manuel Bougot

5) A table designed by Ettore Sotsass for the Golden Eye Exhibition in the Cooper Hewitt Museum, New York. Held in the the mid 1980s, curated by Rajeev Sethi, this show brought renowned international designers to work with master-craftepeople from India on collaborative projects. Courtesy: Museum of Modern Art, New York

_________________

Mayank Mansingh Kaul is a Delhi-based textile and fashion designer. A design curator and writer, he is the Founder-Director of The Design Project India, a not-for-profit organization seeking to enable archival-curatorial-writing projects on Indian design.

Many good points in this article, especially the need for India’s museum of design, to acknowledge references and to ensure that there are spaces where commercialism doesn’t impinge on creativity. A well-written piece which hopefully will provoke some discourse among those involved in creating and designing in India, and those ‘using’ or being inspired by Indian art/design/craft.

Thank you Mayank Mansingh Kaul!